When the British surrendered to the Japanese on 15 February 1942, Australian soldiers were marched to the army barracks at Changi, sixteen miles from the city, which was to be a prisoner of war camp until the Japanese surrendered on 2 September 1945.

At the time of the British surrender, 130,000 British troops including 15,000 members of the 8th Division became prisoners of the Japanese. Members of the 8th Division were marched to Changi on 17 February. Although they were prisoners of the Japanese they remained with their units and military leaders. The 8th Division was housed at Selarang Barracks, previously occupied by the 900 Gordon Highlanders and their families. Consequently, accommodation was cramped and facilities inadequate for the 15,000 soldiers. The first task was to make the area liveable for so many men. The Australian General Hospital was also transferred to Changi.

At Selarang Barracks there was lots of land but the buildings had been damaged during bombing raids. There were no kitchens, no showers, no means of transport and no tools. Wooden huts had to be built to accommodate the men. Food kitchens were built from strips of galvanised iron. Water was obtained from several wells. Latrines had to be constructed drilling holes in the ground using augers.

Chapels were also constructed

As well as making the area that was to be their new home liveable, soldiers were allocated to Japanese working parties, including the erection of a barbed wire fence around the camp. The Japanese organised other working parties of prisoners of war. Fifteen hundred Australians spent eight months in 1942 working on a variety of projects outside the camp including clearing debris in the city and burying Chinese who had been shot by the Japanese.

Access to food for the soldiers was minimal and the food that was provided was of poor quality. The prisoners of war also had to work out how to cook the limited ingredients with some flavour and nutritional value - not an easy task with rice and occasionally small quantities of fish the only ingredients. Grass and some leaves were also boiled in water to be used for additional nutrition. Outbreaks of dysentery occurred periodically.

The men created their own entertainment including concerts presented by unit entertainers and concert parties. An education scheme was established encouraging the prisoners of war to learn something new and reduce boredom. This was not always successful. Over time, the men developed their own language of slang terms for use in the camp.

Another major problem initially was that the men had no access to information about events occurring in the rest of the war until there was finally access to official news bulletins for the Australians in Changi from July 1942. When news that war was ending in Europe reached the camp, there was hope among the prisoners of war that freedom was not far away.

Over three and a half years the men were allowed to send only five postcards home. Each postcard was to contain no more than twenty-four words. The first mail from home was received in March 1943. As well as punishing the prisoners of war, this policy of the Japanese greatly affected family back home who were wondering what had happened to family members.

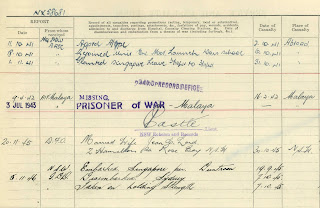

David Lord's service record lists him as being missing in Malaya on 16 February 1942. He is listed as being a prisoner of war on 3 July 1943.

The first mention on the service record of David being in Changi was on 5 September 1945 when he was 'recovered from Japanese at Changi Prison Camp'. On 18 September he was on the ship, 'Duntroon' on his way home to Sydney.

In August 1942 orders from Tokyo arrived stating that all officers above the rank of lieutenant colonel were to be sent to Tokyo.

Life for the men in Changi was not easy but it was much worse for the prisoners chosen for work camps in Burma, Thailand and Borneo. Thousands of men died on these expeditions and those who returned were mere skeletons. An outbreak of cholera had also killed many men in these work parties. Compared with life in these camps, life in Changi was generally better.

However, those living in Changi had to be resilient. To add variety to the inadequate food supply vegetable gardens, large and small, officially, and unofficially, were established. Crops included Ceylon spinach, artichokes, yams, leaf crops, tapioca and sweet potatoes. Some of the men also arranged for goods to come into the camp via the black market after a weak spot was discovered in the fence. Eventually a store was set up in the camp where Australian canned fruit plus local fruit and vegetables could be purchased.

The Australians soon learned that goods required for daily living had to be made themselves. Over time a variety of factories appeared in the camp. These included workshops which turned scraps of metal into utensils needed for everyday living as well as providing a repair and maintenance service. Tools were also made from discarded materials and a variety of goods including razors and sewing machines were made. There was a soap factory and a rubber factory making material suitable for resoling shoes. There was also a pottery making utensils from local clay, a factory for making brooms and another facility for crafting artificial limbs. The Australians also set up a records office monitoring the movements of the Australian prisoners of war.

Trailers were created by stripping unused vehicles, adding a wooden platform then tying rope to the axle and attaching poles for men to pull the vehicle. This was the way goods were transported through Changi.

On 3 September 1942 the Japanese declared that all prisoners of war were to sign a 'Non-Escape Declaration'. The Australian prisoners of war refused and spent three days without food sitting on asphalt until the Japanese agreed to amend the statement that the prisoners had agreed to sign the declaration under duress.

A few of the men had a camera hidden in the camp and took photographs.

The men in Changi were involved in a major project organised by the Japanese - the building of the Changi Airport. The land chosen for this project was largely swamp and the men working on the project had some freedom as many of the Japanese were not interested in supervising a project on such land. Many of the Australians did not mind working on the airport project as they envisaged the day when British and Australian planes would be able to land on the airstrips.

In April 1944 it was announced that the Australians would be moved from Selarang to Changi Prison. The gaol was built for 650 prisoners. It was now to house 5,170 prisoners of war. The men soon started work on once again making an area suitable for crowded habitation. Furniture, buildings water pipes, wire, kitchens, hospitals, forges, power stations, workshops and theatres were all moved on trailers pulled literally by manpower. Again vegetable gardens were established. Monotony, hunger and work became life in the gaol. The amount of food received by the prisoners depended on the amount of work completed each day.

In Changi the Japanese disregarded a number of conditions normally available to prisoners of war - the lack of mail service, refusal to repatriate limbless and wounded men plus an obstructive attitude to any Red Cross relief for prisoners of war.

Towards the end of the war there were air raids on Singapore. The Japanese instructed the prisoners of war to dig tunnels and defence works on Singapore and Jahore. For this work they received extra rations.

Finally on the night of 10 August 1945 news was received on the official and pirate radios that Japan had surrendered. Eventually the prisoners of war were free and able to return home.

Further information:

The Changi Book edited by Lachlan Grant provides a series of first hand accounts of life in the prisoner of war camp and how the men made the best of a bad situation.

Changi - Australian War Memorial

Changi Prison - was it a hell-hole? - Unofficial history of Australian and New Zealand Armed Services.

.jpg)

.jpg)